Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) have revolutionized how we handle signals like images, audio, and 3D scenes. These frameworks, including MLPs with Fourier features, SIREN, and multiresolution hash grids, have been incredibly powerful. However, they all make a critical assumption: that the spectral basis is global and stationary. This means they treat the frequency characteristics of signals as uniform across space, which isn’t always true. Real-world signals often have varying frequency characteristics, with local high-frequency textures, smooth regions, and frequency drift phenomena.

Enter NSTR, or Neural Spectral Transport Representation, a groundbreaking INR framework that explicitly models a spatially varying local frequency field. Developed by Plein Versace, NSTR introduces a learnable frequency transport equation, a partial differential equation (PDE) that governs how local spectral compositions evolve across space. This is a significant departure from existing methods, as it allows for strong local adaptivity and offers a new level of interpretability by visualizing frequency flows.

So, how does NSTR work? It uses a learnable local spectrum field \( S(x) \) and a frequency transport network \( F_θ \) that enforces \( \nabla S(x) \approx F_θ(x, S(x)) \). Essentially, NSTR reconstructs signals by spatially modulating a compact set of global sinusoidal bases. This approach enables the framework to capture the nuances of real-world signals more accurately.

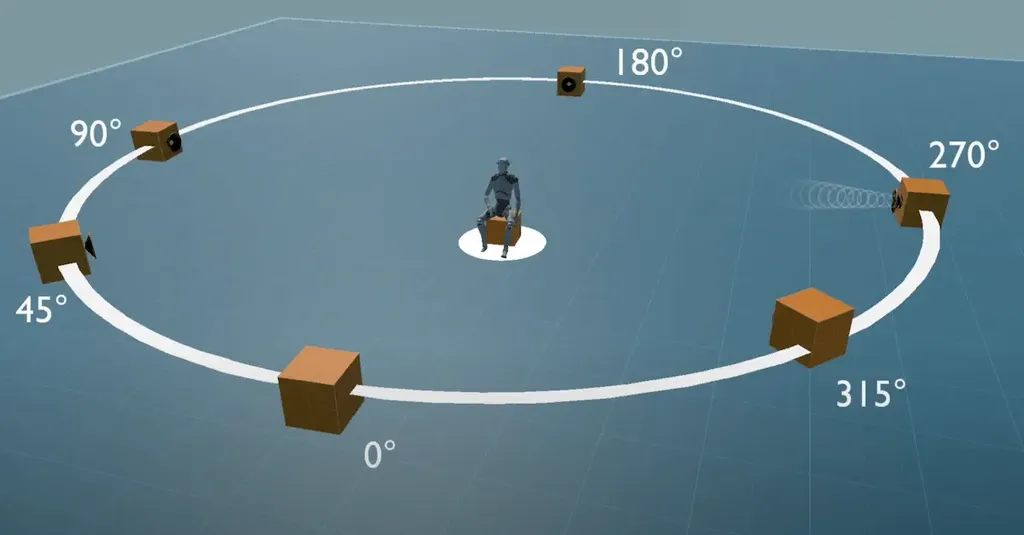

The results speak for themselves. In experiments involving 2D image regression, audio reconstruction, and implicit 3D geometry, NSTR outperformed existing frameworks like SIREN, Fourier-feature MLPs, and Instant-NGP. It requires fewer global frequencies, converges faster, and provides a clearer explanation of signal structure through spectral transport fields.

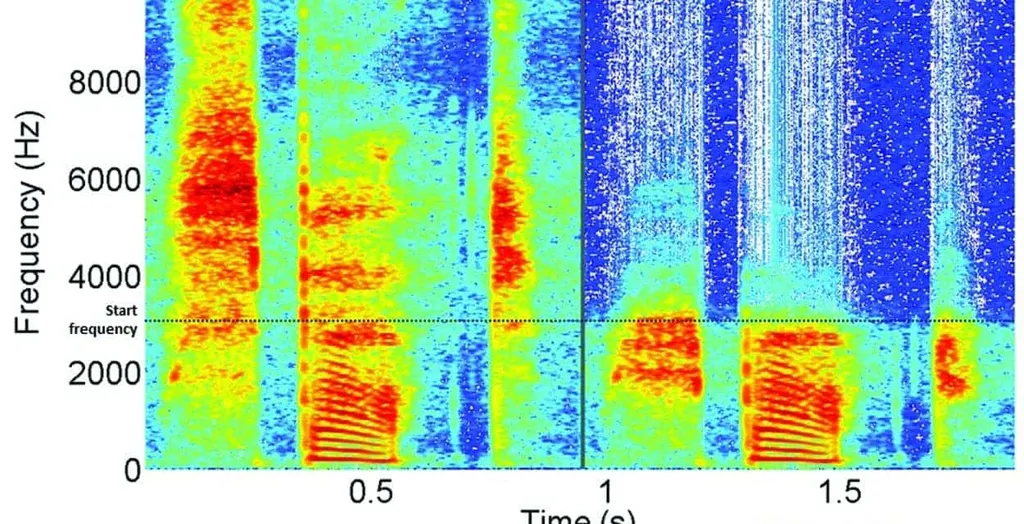

The implications for the music and audio industry are profound. Audio signals, in particular, often exhibit complex frequency variations. Traditional INRs struggle with these variations, leading to less accurate reconstructions. NSTR’s ability to model spatially varying frequency fields could lead to more precise audio processing, enhanced sound synthesis, and improved signal reconstruction. This could be a game-changer for producers and developers working with complex audio signals.

Moreover, the interpretability offered by NSTR’s frequency flows could open new avenues for understanding and manipulating audio signals. By visualizing how frequency characteristics evolve across a signal, researchers and developers can gain deeper insights into the structure of audio data. This could lead to innovative techniques for sound design, audio restoration, and even music composition.

In conclusion, NSTR represents a significant advancement in the field of Implicit Neural Representations. Its ability to model spatially varying frequency fields offers a more accurate and interpretable approach to signal processing. For the music and audio industry, this could mean more precise tools for handling complex audio signals, leading to better sound quality and innovative new applications. The future of audio processing looks brighter with NSTR leading the way.